White People Dont Wanna Go to Art Museums Because There Are Too Many Chinese People

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Ai-Weiwei-portrait-631.jpg)

Concluding year, the editors of ArtReview magazine named the Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei the about powerful artist in the world. It was an unusual choice. Ai'due south varied, scattershot piece of work doesn't fetch the highest prices at sale, and critics, while they admire his achievement, don't care for him every bit a master who has transformed the art of his period. In China, Ai—a brave and unrelenting critic of the authoritarian regime—has spent time in jail, was non immune past the government to leave Beijing for a year and cannot travel without official permission. Every bit a effect, he has become a symbol of the struggle for homo rights in China, but not preeminently so. He is besides quixotic a figure to have developed the moral gravitas of the swell men of conscience who challenged the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century.

So what is information technology about Ai? What makes him, in Western eyes, the world's "most powerful artist"? The answer lies in the West itself. Now obsessed with Cathay, the W would surely invent Ai if he didn't already be. Communist china may after all go the nigh powerful nation in the world. Information technology must therefore have an creative person of comparable event to concord upward a mirror both to China's failings and its potential. Ai (his name is pronounced middle style-mode) is perfect for the part. Having spent his formative years equally an artist in New York in the 1980s, when Warhol was a god and conceptual and functioning art were dominant, he knows how to combine his life and art into a daring and politically charged performance that helps ascertain how we see modern Prc. He'll use any medium or genre—sculpture, ready-mades, photography, operation, architecture, tweets and blogs—to deliver his pungent message.

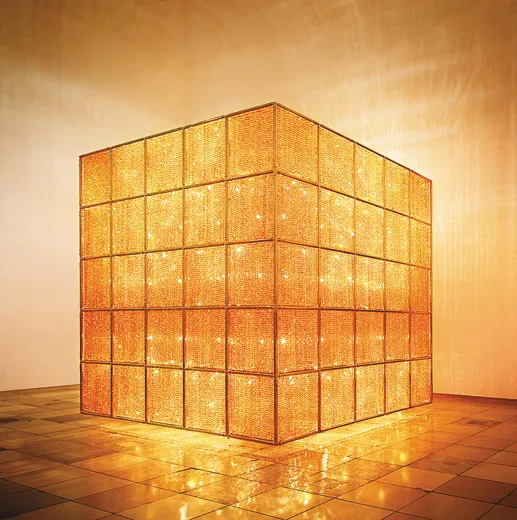

Ai's persona—which, every bit with Warhol's, is inseparable from his art—draws power from the contradictory roles that artists perform in modern civilization. The loftiest are those of martyr, preacher and censor. Not simply has Ai been harassed and jailed, he has also continually chosen the Chinese regime to account; he has made a list, for case, that includes the name of each of the more than 5,000 schoolchildren who died during the Sichuan earthquake of 2008 because of shoddy schoolhouse construction. At the same time, he plays a decidedly unsaintly, Dada-inspired office—the bad boy provocateur who outrages stuffed shirts everywhere. (In ane of his best-known photographs, he gives the White Firm the finger.) Non least, he is a kind of visionary showman. He cultivates the press, arouses annotate and creates spectacles. His signature work, Sunflower Seeds—a work of hallucinatory intensity that was a sensation at the Tate Modern in London in 2010—consists of 100 million pieces of porcelain, each painted by ane of 1,600 Chinese craftsmen to resemble a sunflower seed. Every bit Andy would say, in high deadpan, "Wow."

This year Ai is the subject of two shows in Washington, D.C., an appropriate backdrop for an A-list ability creative person. In the spring, "Perspectives: Ai Weiwei" opened at the Arthur 1000. Sackler Gallery with a monumental installation of Fragments (2005). Working with a squad of skilled carpenters, Ai turned ironwood salvaged from dismantled Qing-era temples into a handsomely constructed construction that appears chaotic on the basis but, if seen from above, coalesces into a map of People's republic of china. (Fragments embodies a dilemma characteristic of Ai: Tin the timber of the past, heedlessly discarded by the present, be recrafted into a Communist china, perhaps a improve China, that we cannot yet discern?) And the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden volition present a wide-ranging survey of Ai'southward work, from October vii to February 2013. The exhibition title—"Co-ordinate to What?"—was borrowed from a Jasper Johns painting.

The question that is not frequently asked is whether Ai, every bit an creative person, is more than just a contemporary phenom. Is Sunflower Seeds, for example, more than a passing headline? Will Ai ultimately matter to China—and to the futurity—as much every bit he does to today's Western fine art globe?

Ai lives in Caochangdi, a village in suburban Beijing favored by artists, where, like an art-king in exile, he regularly greets visitors come up to pay homage to his vision of a improve China. A big, burly human being with a fondness for the neighborhood's feral cats, Ai, who is 55, is disarmingly modest for i who spends and so much time in the public centre. He recently told Christina Larson, an American author in Beijing who interviewed the artist for Smithsonian, that he remains astonished by his prominence. "The clandestine police told me everybody can come across it only you, that y'all're so influential. But I remember [their behavior] makes me more influential. They create me rather than solve the problems I raise."

The authorities proceed him in the news by, for example, hounding him for tax evasion. This past summer, during a hearing on his revenue enhancement case—which he was non allowed to attend—his studio was surrounded by virtually thirty police cars. The story was widely covered. In 2010, he established a studio in a proposed arts district in Shanghai. The regime, fearing information technology would get a middle of dissent—and claiming the structure violated a building code—destroyed information technology early on in 2011. According to Ai, "It made every young person who may or may not have liked me before think I must be some kind of hero."

Ai lives well enough, even under house abort, simply at that place's little almost him that'south extravagant or arty. His house, similar many in the district, is gray and utilitarian. The neighborhood doesn't have much street or café life; it's the sort of place, 1 Beijing resident said, where people get to be left alone. His courtyard home consists of two buildings: a studio and a residence. The studio—a large space with a skylight—has a gray floor and white walls and seems much less chaotic than other artist studios. Both the studio and the residence have a neutral air, as if they have not yet been filled, just are instead environments where an artist waits for ideas, or acts on impulse, or greets cats and visitors. Like Andy Warhol, Ai always has a camera at hand—in his example, an iPhone—every bit if he were waiting for something to happen.

His life seems steeped in "befores" and "afters." Before the modern era, he says, China'southward culture had a kind of "total condition, with philosophy, aesthetics, moral understanding and craftsmanship." In aboriginal China, fine art could become very powerful. "It'south not just a ornamentation or one idea, but rather a full high model which fine art tin can bear out." He finds a similar and transcendent unity of vision in the piece of work of one of his favorite artists, van Gogh: "The art was a belief that expressed his views of the universe, how information technology should be."

His more firsthand earlier, however, is not ancient Cathay but the totalitarian culture into which he was born. Ai's begetter, the renowned poet Ai Qing, ran afoul of the regime in the late '50s and he and his family unit were sent to a labor camp. He spent five years cleaning toilets. (Ai Qing was exonerated in 1978 and lived in Beijing until his death in 1996.) To Ai Weiwei, there was also another, less personal kind of emptiness almost the Communist china of before. "There were almost no cars on the street," he said. "No private cars, only embassy cars. You lot could walk in the middle of the street. It was very slow, very tranquillity and very gray. In that location were not and so many expressions on human faces. Later the Cultural Revolution, muscles were yet not built upward to laugh or show emotion. When you saw a trivial flake of colour—like a yellow umbrella in the rain—information technology was quite shocking. The order was all grey, and a petty bit blue."

In 1981, when it became possible for Chinese citizens to travel abroad, Ai made his way to New York. His first glimpse of the city came on a plane in the early evening. "Information technology looked like a basin of diamonds," he said. It was not the city'due south cloth wealth that attracted him, however, but its dazzling freedom of activity and speech communication. For a time Ai had an apartment near Tompkins Square Park in the East Village, where young Chinese artists and intellectuals oft gathered. But he had no particular success as an artist. He worked odd jobs and spent his time going to exhibitions. The poet Allen Ginsberg, whom he befriended, told Ai that galleries would not take much notice of his piece of work.

Although he has a special interest in Jasper Johns, Warhol and Dada, Ai is not easily categorized. He has a wandering mind that can embrace very different, sometimes reverse, elements. The aforementioned artist who loves the transcendental oneness of van Gogh, for instance, too admires the abstruse and sometimes analytical sensibility of Johns. Much of Ai's all-time-known work is rooted in conceptual and Dadaist fine art. He has often created "set up-mades"—objects taken from the earth that an artist then alters or modifies—that have a strong satirical element. In one well-known case, he placed a Chinese figurine inside a canteen of Johnnie Walker Scotch. Notwithstanding in dissimilarity to many conceptual artists, he too demonstrated, early, a great involvement in a work'due south visual qualities and sent himself to study at the Parsons School of Blueprint and the Art Students League in New York.

Ai's interest in design and compages led him, in 2006, to collaborate with HHF Architects on a country business firm in upstate New York for two immature art collectors. The business firm is four equal-sized boxes covered on the exterior in corrugated metallic; the small spaces between the boxes permit light to suffuse the interior, where the geometry is too softened past wood and surprising angles. The honour-winning blueprint is both remarkably simple and—in its use of light and the grouping of interior spaces—richly circuitous.

But Ai's interest in design and architecture has less to do with being a conventional architect than with rebuilding—and redesigning—China itself. Returning to China in 1993, when his father fell ill, he was discouraged by two new forms of oppression: way and cronyism. "Deng Xiaoping encouraged people to get rich," he said, adding that those who succeeded did so through their affiliation with the Communist Party. "I could meet and so many luxury cars, but at that place was no justice or fairness in this society. Far from information technology." New consumer goods such as tape recorders brought fresh voices and music into a moribund civilisation. But rather than struggle to create contained identities, Ai said, young people instead settled into a new, easy and fashion-driven conformity. "People listened to sentimental Taiwanese pop music. Levi'southward blue jeans came in very early. People were seeking to exist identified with a sure kind of style, which saves a lot of talking."

Ai responded to the new China with scabrous satire, challenging its puritanical and conformist character past regularly showcasing a rude and boisterous individuality. He published a photo of himself in which he is shown naked, leaping ludicrously into the air, while belongings something over his genitals. The photo caption—"Grass mud horse covering the middle"—sounds in spoken Chinese like a coarse jest near mothers and the Key Committee. He formed a corporation called "Beijing Fake Cultural Development Ltd." He mocked the Olympic Games, which, in China, are at present a kind of country religion. The CCTV belfry in Beijing, designed by the celebrated Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, is regarded with keen national pride; the Chinese were horrified when a burn swept through an addendum and a nearby hotel during construction. Ai's response? "I think if the CCTV building really burns down it would be the modern landmark of Beijing. Information technology can represent a huge empire of ambition burning down."

Ai'due south resistance to all forms of control—capitalist and communist—manifests itself in one poignant fashion. He refuses to listen to music. He associates music with the propaganda of the old days and prefers the silent spaces of independent thought. "When I was growing up, we were forced to listen to merely Communist music. I think that left a bad impression. I have many musician friends, but I never heed to music." He blames the Chinese educational organization for failing to generate any grand or open-ended sense of possibility either for individuals or the society as a whole. "Education should teach you to call back, just they only want to control everyone'southward heed." What the regime is virtually agape of, he says, is "free discussion."

Ai will occasionally say something optimistic. Perchance the Cyberspace will open upwards the discussion that schools now restrain, for example, even if the blog he ran has been shut down. For the most office, though, Ai's commentary remains bleak and denunciatory. Few people in People's republic of china believe in what they are doing, he says, not even the secret police. "I've been interrogated by over eight people, and they all told me, 'This is our job.'...They do non believe anything. Only they tell me, 'Yous can never win this state of war.'"

Not soon anyhow. In the West, the artist as provocateur—Marcel Duchamp, Warhol and Damien Hirst are well-known examples—is a familiar figure. In a China only emerging as a earth power, where the political regime prize conformity, discipline and the accumulation of riches, an artist working in the provocative Western tradition is still regarded as a threat. Chinese intellectuals may back up him, but the Chinese by and large take no more agreement of Ai than a typical American has of Duchamp or Warhol. "There are no heroes in modern Mainland china," Ai said.

The Westward would like to plow Ai into a hero, simply he seems reluctant to oblige. He lived in postmodern New York. He knows the celebrity racket and the hero racket. "I don't believe that much in my own answer," he said. "My resistance is a symbolic gesture." But Ai, if not a hero, has found ways to symbolize certain qualities that China may one mean solar day celebrate him for protecting and asserting. Costless discussion is one. An out-there, dark and Rabelaisian playfulness is another. Only the near interesting quality of them all is found in his best works of art: a prophetic dream of China.

Much of Ai'southward art is of just passing involvement. Similar so much conceptual art, it seems little more a diagram of some pre-conceived moral. Art with a moral too often ends with the moral, which can stopper the imagination. Consider Ai's amusing and well-known Johnnie Walker piece. Is it suggesting that China is enveloped within—and intoxicated past—Western consumer civilization? Of course it is. One time yous've seen it, you don't take to think most it anymore. Jokes, even serious jokes, are like that. They're not equally good the second time around.

Simply several Ai works are fundamentally dissimilar in character. They're made of more than morals and commentary. They're open up-ended, mysterious, sometimes utopian in spirit. Each calls to mind—equally architecture and pattern tin—the birth of the new. The oddest instance is the "Bird'southward Nest" stadium of the 2008 Olympics. While an impassioned critic of the propaganda effectually the Olympics, Ai nonetheless collaborated with the architects Herzog & de Meuron in the design of the stadium. What kind of Communist china is being nurtured, i wonders, in that spiky nest?

According to Ai, governments cannot hide forever from what he calls "principles" and "the true statement." He decries the loss of religion, aesthetic feeling and moral judgment, arguing that "this is a large infinite that needs to be occupied." To occupy that infinite, Ai continues to dream of social transformation, and he devises actions and works that evoke worlds of possibility. For the 2007 Documenta—a famous exhibition of contemporary art held every five years in Kassel, Frg—Ai contributed 2 pieces. One was a monumental sculpture called Template, a chaotic Boom-boom of doors and windows from ruined Ming and Qing dynasty houses. These doors and windows from the past seemed to atomic number 82 nowhere until, oddly enough, a storm knocked down the sculpture. His 2d contribution was a work of "social sculpture" called Fairytale, for which he brought ane,001 people from Cathay—chosen through an open up weblog invitation—to Documenta. He designed their clothes, luggage and a place for them to stay. But he did non point them in any particular management. On this unlikely trip through the wood, the Chinese pilgrims might find for themselves a new and magical world. They too might notice, as Ai did when he went to New York, "a bowl of diamonds."

Sunflower Seeds, his most celebrated work, yields like questions. The painting of and then many individual seeds is a slightly mad bout de force. But the scale of the work, which is at once tiny and vast—raindrop and sea—seems no crazier than a "Made in China" consumer society and its bottomless desires. Does the number of seeds reflect the dizzying corporeality of money—millions, billions, trillions—that corporations and nations generate? Do the seeds simultaneously propose the famines that mark Chinese history? Do they evoke China'southward brief moment of cultural liberty in 1956 known every bit the "Hundred Flowers Entrada?" Do they represent both the citizen and the nation, the individual and the mass, endowing both with an air of germinating possibility? Will China always blossom, ane wonders, with the joyful intensity of van Gogh'due south sunflowers?

Christina Larson in Beijing contributed reporting to this story.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/is-ai-weiwei-chinas-most-dangerous-man-17989316/

0 Response to "White People Dont Wanna Go to Art Museums Because There Are Too Many Chinese People"

Post a Comment